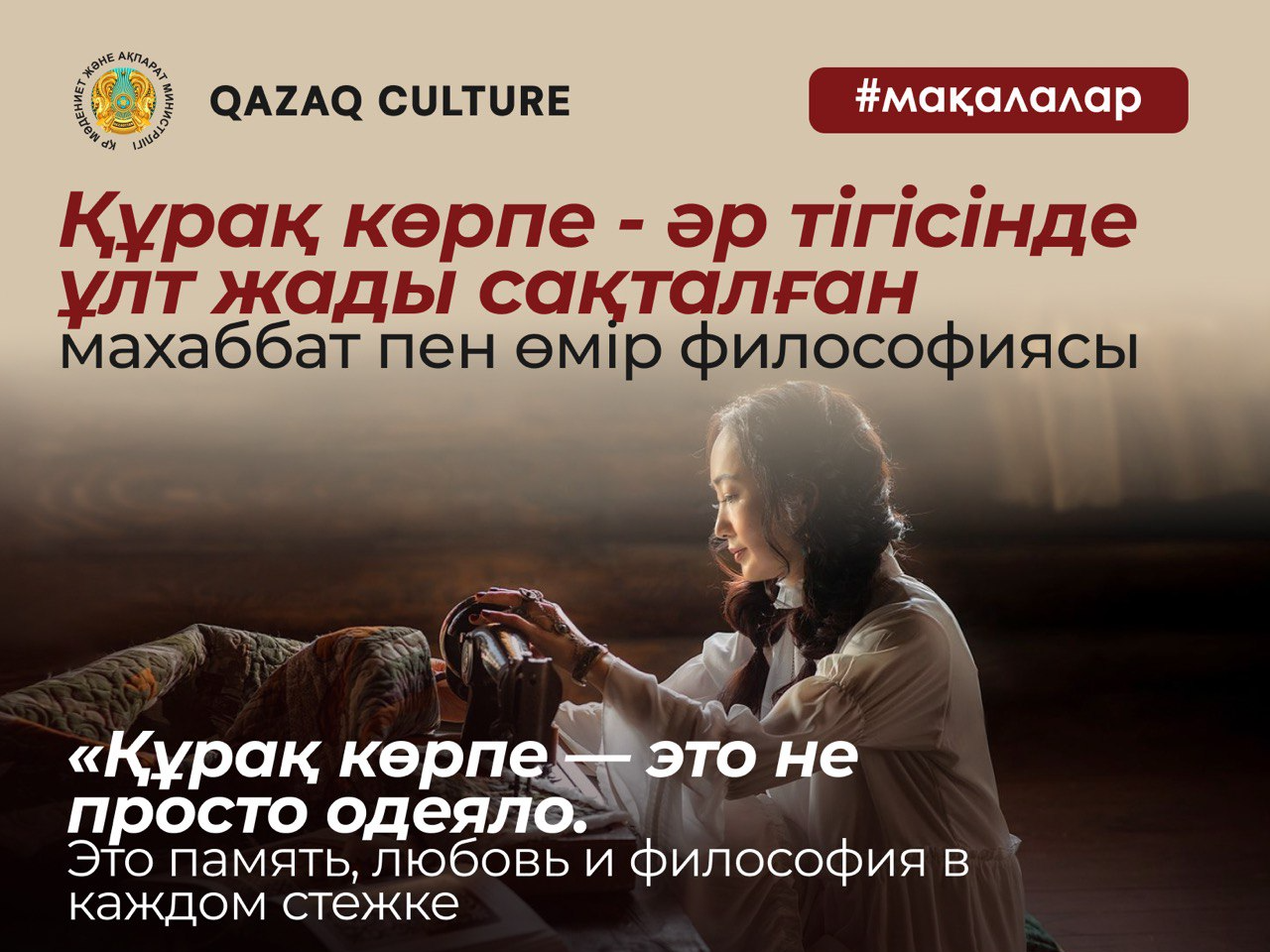

"Kurak körpe is not just a blanket. It is memory, love and philosophy in every stitch

Her workshop Ay.UKi in Astana smells of fabrics, freshly brewed tea and warm memories of childhood. Here, among colorful patches and soft lamplight, kurak korpe are born - blankets in which ancient Kazakh traditions, personal stories and the energy of a woman's soul are intertwined. Our heroine Aigerim Orazbek tells how her childhood curiosity about her grandmother's chest grew into a business that became her mission - to preserve and rethink folk crafts.

Aigerim, do you remember the moment when you first sat down at a sewing machine? What did you feel then?

- Yes, of course I remember. Every summer my parents sent me to a village near Shymkent to my native Kulimkhan apa. She was sitting on the floor, sorting through pieces of cuts - "zhyrtys" from the "Kudai tamak" funeral, beautiful fabrics from "uilenu toy" or "sundet toy". She cut some, and carefully put others in a chest. I still remember this smell and the evenings when apa consulted me about colors, unobtrusively introducing me to Kazakh crafts.

In Temirtau, where I lived, there were almost no traditions, and in the late 90s, it was not easy in the city. At 14, my mother sent me to courses in cutting, sewing and embroidery so that I could dress beautifully. Then I sewed for myself and my friends, but later life took me aside - study, marriage, children, work.

And how did everything continue then? Did you devote yourself to everyday life?

- Yes, but the soul always required fulfillment. When the children grew up, in 2017 I got out the machine again. I found the master Gulmira Ualikhan on Instagram and took her course on kurak korpe with American cotton. These bedspreads are bright, cozy and practical. For me, this is nostalgia, a search for myself, and the call of tradition. Each bedspread is like a tribute to my ancestors.

Was it scary to start? Did you have any doubts?

- No. For me, this is an art with a deep meaning. My korpe conveys love for everything native. I also study culture through language, cuisine, books and other crafts. I believe that each product contains a caring maternal essence and feminine creativity.

There are many artisans on the market who are into this kind of creativity. How does your approach differ from the traditional and mass ones?

- I sew individually and choose the clients myself. It takes me 3-4 months to create each bedspread. While working, I can sing or dance — the main thing is to feel calm inside.

Was there a blanket with a special story?

Yes. This year I sewed a kurak korpe for young Lyazzat as a dowry. In the fall, this blanket became part of the production of the Gulder ensemble — both the master and the patterns came to life in the dance. It was very touching.

You have a lot of clients who come from abroad or star artists. Do you remember any special reactions from clients?

Yes, I remember Aigul Balkhan insisted that I personally give the blanket to her daughter. It was like an initiation — the transfer of wisdom and love from a mother through tradition. For me, this is a special gesture.

Let's philosophize. More and more often, our generation has begun to reach out to the roots. Do you think that Kazakh culture is experiencing a renaissance?

- Yes. Even in the era of globalization, we are reviving crafts that preserve care, love and family values. We have become more drawn to our roots, study the culture of our ancestors, honor the traditions of our ancestors and, in general, understand our cultural code. This is pleasing. But again, this all comes with age, experience and wisdom. And you want to share it.

Do you think this is why people today are drawn to handmade things?

- Of course. They have soul and energy. We feel a connection with our ancestors at the genetic level.

And what do you feel when you sew “kurak korpe”? Can this be called a way of healing?

- Yes. Working with ornament and geometry is calming, and gratitude for the finished product brings happiness.

If you were to describe yourself in three words, who are you?

Beloved granddaughter of her Kulimkhan apa, caring mother and wise future grandmother.

And I also like the phrase: "When a person does something, he seems to talk to the world without words." I want my work to make the world understand that we have something to say, we have a deep history and foundations that are worth learning from. They give us a second wind. A breath to live.