Казахстанские степи Дарьи Швалевой

Daria, is this your second exhibition in Kazakhstan?

Yes, that's right. The first one was in collaboration with the Kulanshi Gallery and Leila Mahat in 2022. I warmly recall the first exhibition and the first meeting with the audience in Astana, and I am glad that today I was able to present my works for the second time in the original and beautiful space of the Sal Seri Gallery.

Tell us a little about yourself. Where did you live before moving to Kazakhstan?

I am a real nomad. My childhood and youth were spent in the Urals, in Perm. Then I studied in France and worked for 10 years at the Museum of History and Art of the city of Saint-Denis. I found myself as an artist in Kyiv, Ukraine, where I discovered printmaking. And my first exhibitions took place in Bucharest, Romania in 2019-20.

How did you get into printmaking? What was the beginning like?

When we left France in 2014 and I left the museum, I was looking for myself in creativity. I started with painting, with pastels. I even tried my hand at pottery. Although I myself felt and understood that graphics and drawing were closer to me. I was lucky to find myself in Kyiv, where there are many strong artists and a unique creative environment. There I met Anna Khodkova and Kristina Yarosh, two extraordinarily talented contemporary graphic artists. And I was fortunate enough to work and study in their workshop in a variety of printmaking techniques. I continue to learn now.

How do you create your works?

I work on an etching machine. This is an impressive machine. I affectionately call it "my ship", because the machine has a wheel, like a steering wheel, that you need to turn to get a print. And for each job, I need to do this from one to five times. I work in various techniques: drypoint engraving, cardboard engraving, collagraphy, monotype, often I mix them in one work. Here at the exhibition there are also works printed manually, without a machine. For example, my linocuts. I use metal, plastic, cardboard in my work. Now in the world of printmaking there are many materials and different techniques: from traditional to experimental and new.

What brought you to Kazakhstan? You moved in 2020, didn't you?

Yes, it was in 2020. I came with my family thanks to the opportunities that work opened up for us, and this was certainly not accidental. We were very interested in discovering Kazakhstan.

Did you breathe your new creative inspiration from our Kazakh steppe?

Before coming to Kazakhstan, I had never been to Central Asia and for me there were many discoveries here. I was struck by the people of Kazakhstan, their love of freedom, openness and kindness. I was impressed by the culture of the Kazakhs as nomads, extraordinarily rich and unique. And, of course, I discovered the Kazakh steppe for myself. The steppe is a special element, as strong as the sea or mountains. It has a spirit of freedom, space. It is always different and always amazing. I traveled a lot around Kazakhstan by trains, my family and I "traveled" across the steppe to the North and East, more than once we got to the city of Almaty through Lake Balkhash and lived in the mountains in Merke. I wanted to share what I saw in my works. But in order to pass what I saw through myself, so that it was filled with real meaning, and not remain a postcard, I needed to immerse myself in the history of these places.

Studying the history of the last centuries, you very quickly come to dramatic pages: the colonization of the Kazakh steppes by the Russian Empire, suppressed uprisings, the civil war, collectivization, the Holodomor, the deportation of Kazakhs and the forced resettlement of other peoples to Kazakhstan, camps, wars. I see how the wounds of the past and the crimes of the Soviet era are reflected today. And at the same time, I am very happy that Kazakhstanis know and study their history and that now Kazakh culture and language are experiencing a new flourishing.

How did you immerse yourself in Kazakh culture and history? What books were important to you?

I really love the Kyrgyz writer Chingiz Aitmatov, for me he is the greatest humanist. I have been familiar with his books since my youth, and here I read his novel "And the Day Lasts Longer than a Century", which takes place in Kazakhstan, in the steppe, in a small village near the railway. This is a very powerful book. It weaves together several lines of narrative, touching on many topics that are still relevant today: state violence and war, human dignity and baseness, love (in all its forms), nature and human relations with it, heritage and progress. Aitmatov's father was repressed, shot when he was very young, and Chingiz searched all his life for the place of his burial. In this book, he shows how terrible the Soviet regime was, because it encroached not only on human life, but on his dignity, memory and humanity, and that good, like evil, is always created by people.

Then, thanks to a meeting with the wonderful Astana book club Senu, I read the novel "Noon" by the writer Talasbek Asemkulov, translated by Zira Nauryzbay. In his novel, I saw a special way of thinking of the Kazakhs, which was associated with steppe life, with nature. I felt its beauty. I was also touched by the kind, respectful attitude in Kazakh society towards all its members, whether it be just a neighbor or a child. I learned a lot about the tradition of the almost sacred art of the blacksmith and kyushi. "Noon" also tells about the tragic events of the 20th century. For example, how a whole generation of kyushi was practically lost due to repression, famine, and war. In this autobiographical book, Asemkulov tells how his grandfather (in life Zhunusbay Stambaev), returning to his village after the war and Soviet camps, took him for upbringing as a baby from his daughter in order to pass on his art of playing the dombra.

I really fell in love with Kazakh music, the beauty and magical power of the dombra and kobyz. On the opening night of the exhibition, the kobyz was played by the amazing kyushi of our time - Raushan Orazbay, and the beautiful vocalist Asem Esenova performed Shakir Abenov's song "Daua".

Your work vividly reflects the theme of the repressions of the 20th century. Even in the first exhibition, you singled out your work "Reed Pain". Why is it dear to you?

Yes, this theme served as a subtext for many of my works. "Reed Pain" was one of the first. In it, the reed, so familiar to us in the steppe landscape, became an image of human destinies. I came to these broken lines. And there are broken ones, there are lonely ones, there are those that lean against each other.

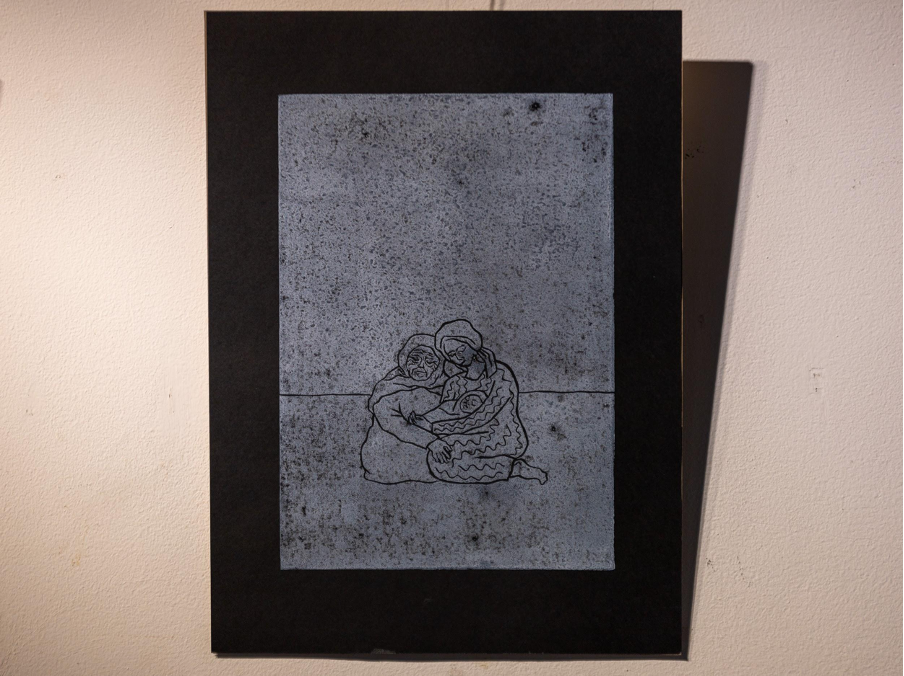

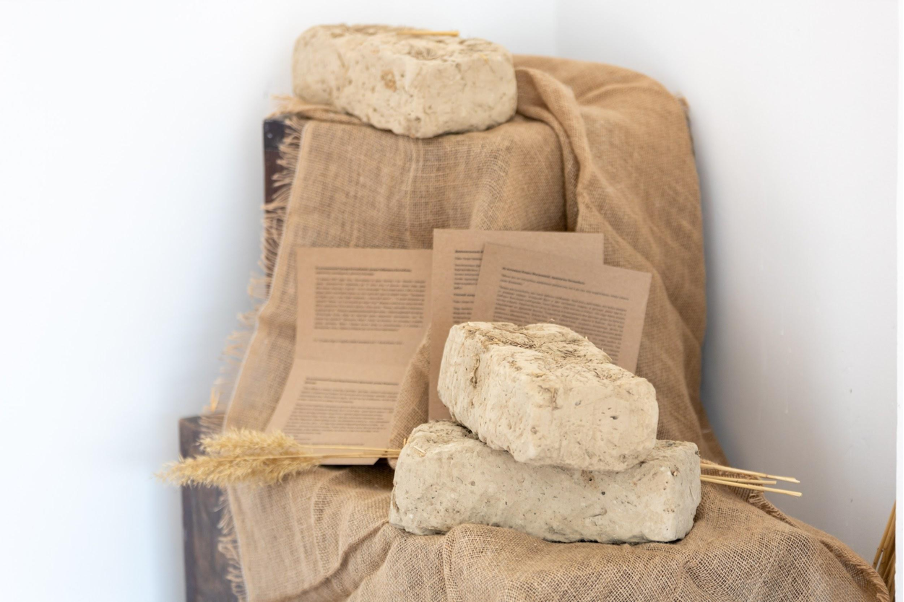

Reed also appears in other works presented at the exhibition: "Memories", "Whisper of the Reed", "Loneliness", "Sheaves" and, finally, "Adobe Mountain". In these works, I thought about the fate of women in this terrible era. Women who buried their husbands, or looked for them, not knowing their fate, who were separated from their children, deprived of youth, the joy of motherhood, who were tortured by hard labor and hunger in camps, special settlements, collective farms.

The barracks were heated with reeds. Teachers, musicians mixed clay with reeds for adobe bricks, from which these barracks were built. It was very hard work, the norms were huge. It was very important for me that there were these adobe bricks at the exhibition, which we no longer see in the modern city. I managed to bring them by train from the southern town of Shu.

Repressions and tragedies of the 20th century also affected my family. My great-grandfather was shot in 1938 at the age of 37. My great-grandmother was supposed to end up in the Akmola camp. (ALZHIR - Akmola camp for wives of traitors to the Motherland. Located 40 kilometers from the capital of Kazakhstan) She was considered the wife of an enemy of the people. Her three-year-old child, my grandmother, was supposed to end up in an orphanage. But we can say that they were lucky, they were warned that they needed to run. They were told to drop everything and run. And somehow by relays and trains they got to the Urals from the Bryansk region.

Some of my works touch on the topic of collectivization. During the years of collectivization, the Kazakhs were deprived of the most precious thing, what constituted the basis of the life of nomadic peoples - livestock. Many tried to flee from the Kazakh steppe to save themselves, their relatives and their livestock, often dying along the way. This is one of the meanings of my work "My Grandfather's Yak"

Camels in my graphics could only appear in the steppe. These are partly Aitmatov's camels, he has them so colorful in the book "And the Day Lasts Longer than a Century", he describes them so interestingly, I could not help but draw them.

Now I conduct tours for students in the gallery, telling them about my work. The plan is to organize a meeting master class here, where I can tell you more about the materials, techniques of modern printmaking and about my favorite machine.

You can get acquainted with the work of Daria Shvaleva in the Sal Seri Gallery at the address: Astana, st. Heydar Aliyev 10/1